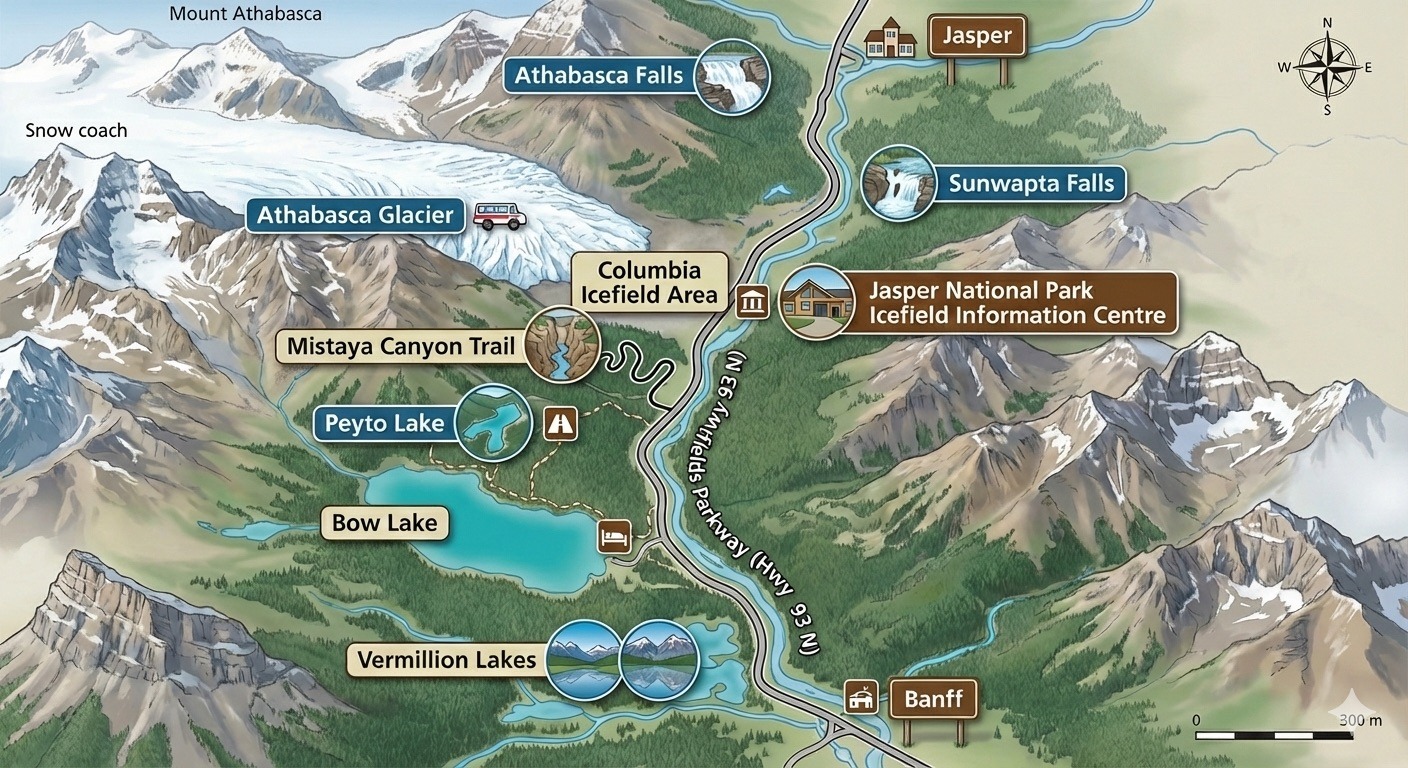

The Icefields Parkway (Highway 93 North) regularly lands on “world’s most beautiful drives” lists, and after driving it, you’ll understand why. This 232-kilometre ribbon of highway connects Banff and Jasper National Parks—driving it means threading past ancient glaciers, thundering waterfalls, and lakes so impossibly blue they look like someone cranked up the saturation. It’s the kind of drive where you’ll pull over constantly, camera in hand, wondering if what you’re seeing is actually real.

Can you do it in a day? Yes—this one-day itinerary covers the must-see stops without rushing. The driving time is about three hours if you somehow resist stopping, but the whole point is to stop. A lot. Leave early from Banff, and you’ll roll into Jasper by late afternoon with a memory card full of photos and that particular kind of tired that comes from a day well spent.

And then there’s the wildlife. The Icefields Parkway cuts through some of the most pristine habitat in North America, and you’re genuinely likely to see animals along the way. Black bears forage in roadside meadows, grizzlies occasionally appear on distant slopes, and bighorn sheep often congregate near the highway—sometimes right on it, completely unbothered by traffic. Mountain goats pick their way across impossibly steep terrain, elk graze in the valleys, and if you’re lucky, you might spot a moose near one of the wetland areas. Keep your camera accessible, drive slowly around blind corners, and give animals plenty of space. This is their home; we’re just passing through.

A few things to sort before you go: fill up your tank in Banff or Lake Louise, because the only other gas station is at Saskatchewan River Crossing about 135 km in—and they know they’re your only option, so prices reflect that. Cell service disappears after Lake Louise and doesn’t really come back until Jasper, so download your maps and playlists beforehand. And you’ll need a Parks Canada pass, but if you’ve already got one for Banff, you’re covered for the entire drive.

Respect the Environment

🌿 The Icefields Parkway passes through protected wilderness that’s been relatively unchanged for thousands of years. Keeping it that way means being mindful of how we move through it. The Leave No Trace principle is simple: take only photos, leave only footprints. Pack out everything you bring in—every wrapper, every tissue, every apple core. Stay on marked trails to protect fragile alpine vegetation that can take decades to recover from a single footprint.

🦌 Wildlife encounters are part of what makes this drive special, but they come with responsibility. Parks Canada requires you to stay at least 30 metres (about three bus lengths) from elk, moose, deer, sheep, and goats, and at least 100 metres (ten bus lengths) from bears, wolves, and cougars. If an animal approaches you, it’s your responsibility to back away. The only exception is viewing from inside a legally parked vehicle. Violating these distances can result in fines up to $25,000—but more importantly, approaching wildlife habituates them to humans, which rarely ends well for the animal.

⚠️ In 2024 alone, multiple bears in the Banff area had to be euthanized after becoming too comfortable around people. A black bear in Banff town was put down in May after it stopped responding to hazing attempts. Another young bear in nearby Canmore was killed in August after repeatedly feeding in residential areas and refusing to leave. These aren’t rare exceptions—they’re the predictable outcome when wildlife learns to associate humans with food. A fed bear is a dead bear. Keep food secured, don’t leave garbage accessible, and never, ever feed wildlife deliberately.

🔥 Fire safety deserves the same seriousness. In July 2024, dry lightning ignited what became the most devastating wildfire in Canadian national park history. The Jasper wildfire burned 32,722 hectares, destroyed 358 structures in the town of Jasper, and killed one firefighter. Driving north on the Parkway today, you’ll pass 50 kilometres of burnt forest—a stark reminder of how quickly these mountains can change. If you’re camping, fires are only permitted in designated metal fire pits with a valid permit, and only firewood purchased locally (to prevent invasive species). During high fire danger, bans can be implemented at any time. Check albertafirebans.ca before your trip, and report any smoke or illegal campfires to Banff Dispatch at (403) 762-1470.

Weather and Road Conditions

Mountain weather is its own creature. It’s entirely possible to leave Jasper under blue skies and hit a blizzard at the Columbia Icefield an hour later. The Icefields Parkway crosses high elevation passes where conditions can change dramatically and without warning—snow is possible in any month at the higher elevations, and summer thunderstorms can roll in fast.

The best time to drive the Icefields Parkway is mid-June through early October, when roads are clear and all facilities are open. The shoulder seasons—May and October—offer beautiful scenery and fewer crowds, but they also bring unpredictable conditions. By mid-October, snow and ice on the road surface are common, and winter conditions can set in quickly. From November 1 to April 1, tires marked with either the M+S (Mud and Snow) symbol or the Three-Peak Mountain Snowflake symbol are legally required. Here’s the catch: most all-season tires carry the M+S symbol, so they’re technically legal—but M+S is a tread pattern rating, not a cold-weather performance rating. Below +7°C, standard all-season rubber hardens and loses grip on the compact ice that covers the Parkway. True winter tires—marked with the Three-Peak Mountain Snowflake symbol—use rubber compounds that stay soft and grippy in freezing temperatures. If you’re renting, specifically request winter tires (not just “winter legal”). Most agencies charge an extra $15-30 per day, but on a road where conditions change fast and help is hours away, it’s worth every cent. The Parkway is not maintained as a major highway, and Parks Canada doesn’t recommend using it as a winter alternative to the Trans-Canada Highway system.

One thing to watch: navigation apps like Google Maps may suggest the Parkway as a shortcut, especially in winter. It’s not. If you’re just trying to get between Calgary and Edmonton without sightseeing, take the Trans-Canada Highway (Highway 1) instead—it’s cleared around the clock and has services along the way. The Parkway is for people who want to experience it, not bypass it.

Unlike major highways, the Parkway is maintained with sand rather than salt to protect the surrounding ecosystem and wildlife. This is better for the environment but means the road surface can be slipperier than you’d expect—even in conditions that look manageable, there may be less traction than you’re used to.

Avalanche risk runs from late fall through midwinter, and sections of the road can close with short notice—sometimes for hours, sometimes for days. In winter, snowplows operate between 7 AM and 3:30 PM, so plan to travel during daylight hours. Closure gates are located at several points along the Parkway, including near Athabasca Falls, Sunwapta, Parker Ridge, and Saskatchewan River Crossing.

Before you head out, check current conditions at 511.alberta.ca or call 511 from within Alberta (or 1-855-391-9743 from anywhere in North America). The Canadian Rockies region page shows real-time alerts and closures. Since there’s no cell service along most of the Parkway, check conditions before you leave and let someone know your plans. In winter, if conditions look marginal, they probably are—there are no services between Lake Louise and Jasper, and getting stuck in a storm 100 kilometres from either town is a serious situation.

In winter, treat the Parkway like backcountry driving. Pack a proper emergency kit: sleeping bags or heavy blankets, extra warm clothing, food, water, a flashlight, and a full tank of gas. If conditions deteriorate or the road closes behind you, you might be waiting hours for help with no cell service to call for it.

Before you go, confirm you have roadside assistance with at least 200 km towing coverage. Options include AMA (Alberta Motor Association), Canadian Tire Roadside Assistance, or coverage through your credit card or vehicle insurance. There are no garages between Banff and Jasper, and without coverage, a breakdown could mean a tow bill in the hundreds of dollars—on top of being stranded with no cell signal. If you’re renting, ask the company specifically what to do if the vehicle breaks down on the Parkway before you leave the lot.

Top Attractions Along the Icefields Parkway (Banff to Jasper)

Can you do it in a day? Yes—this one-day itinerary covers the must-see stops without rushing. The driving time is about three hours if you somehow resist stopping, but the whole point is to stop. A lot. Leave early from Banff, and you’ll roll into Jasper by late afternoon with a memory card full of photos and that particular kind of tired that comes from a day well spent.

Johnston Canyon

Before you even hit the Icefields Parkway proper, there’s a detour worth making. Johnston Canyon sits along the Bow Valley Parkway (Highway 1A), the scenic back road that winds between Banff and Lake Louise through some of the park’s richest wildlife territory. This montane ecosystem is one of the first areas to green up each spring, which means it’s prime habitat for bears, wolves, and elk—and one of the reasons Parks Canada takes access seriously here.

Here’s the thing about timing: from March through late June, a 17-kilometre section near Johnston Canyon closes nightly from 8 PM to 8 AM to give wildlife space during their most active hours. Spring and fall also bring daytime vehicle restrictions for a cycling pilot program, so check Parks Canada’s website before you plan your route. The fines for ignoring closures can hit $25,000, so it’s worth knowing the schedule.

But once you’re there, the canyon delivers. You’ll walk on catwalks bolted directly into the limestone walls, the turquoise Johnston Creek churning below your feet. About 1.1 km in, you’ll reach the Lower Falls through a natural tunnel carved into the rock—most people spend about 20-30 minutes getting there, though the views make it easy to linger. The Upper Falls add another 1.6 km if you’ve got time, and they’re worth the extra effort.

Summer means rushing waterfalls and lush canyon walls, but it also means crowds—this is one of Banff’s most popular hikes, so arriving before 8 AM or after 6 PM makes a real difference. Winter, though, is when the canyon transforms into something almost otherworldly: frozen waterfalls, ice-coated walls, and guided ice walks that run from December through April. You’ll need cleats or microspikes, but walking through a frozen canyon is an experience that stays with you.

Lake Louise and Moraine Lake

These are the postcard lakes—the ones plastered across every Canadian tourism campaign, and for good reason. Lake Louise sits beneath Victoria Glacier with the iconic Fairmont Chateau on its shore, while Moraine Lake is tucked into the Valley of the Ten Peaks, surrounded by some of the most dramatic mountain scenery in the Rockies. Both are absolutely worth seeing, but here’s the honest truth: if you’re doing a day trip to Jasper, you might want to save these for another time.

Both lakes deserve unhurried exploration. The shuttle systems, the parking logistics, the crowds—it all takes time to navigate, and rushing through them means missing what makes them special. If you’re set on squeezing them in, aim for a very early start and pick just one lake. But if you can, give them their own day.

For everything you need to know about visiting—shuttle reservations, parking strategies, the best times to beat the crowds—check out our Lake Louise and Moraine Lake Day Trip Guide.

Bow Lake

About 40 km north of Lake Louise, you’ll round a bend and Bow Lake will appear almost without warning—a vast turquoise expanse spreading out below the Bow Glacier, with mountains rising sharply on either side. It’s one of those moments where you pull over and just stand there for a minute, taking it in.

What makes Bow Lake special is how accessible it is. The parking lot sits right beside the shore, so within seconds of leaving your car, you’re standing at the water’s edge. The Lodge at Bow Lake perches on the lakeshore with its distinctive red roof—it makes for a great photo and anchors the scene beautifully. Wander along the rocky beach, skip some stones, watch the glacier reflected in the still morning water. Most people spend 15-30 minutes here, though you could easily lose more time if the light is right.

Morning is magic at Bow Lake. The sun illuminates the glacier, the water is often calm enough for perfect reflections, and you’ll likely have more space than you would at the more famous Peyto Lake down the road. If you’ve got time for a longer adventure, a trail leads to Bow Glacier Falls—about 4.5 km each way through increasingly dramatic scenery.

In summer, the lake glows that famous glacial turquoise. Winter brings a different kind of beauty: frozen shores, dramatic clouds, and a quiet that’s hard to find in peak season. The lodge closes for winter, but the road stays open year-round, weather permitting.

Peyto Lake

If you’ve seen one photo of the Canadian Rockies, there’s a good chance it was this view. Peyto Lake’s distinctive wolf-head shape, that almost unreal turquoise colour, the peaks framing it perfectly—it’s become the defining image of the Icefields Parkway for good reason. The Peyto Lake viewpoint sits at Bow Summit, the highest point along the entire highway at 2,069 metres, and on a clear day the scene genuinely looks photoshopped.

The lake is named after Bill Peyto (pronounced “pee-toe”), one of the most colourful characters in Banff’s early history. Starting in 1913, Peyto worked as a trail guide and one of the park’s first wardens, helping establish many of the routes still hiked today. Known for his rugged demeanour and deep love of the wilderness, he’s exactly the kind of person you’d want a spectacular lake named after. The glacier feeding it bears his name too. Before European exploration, this area held deep significance for Indigenous peoples including the Stoney Nakoda, whose ancestors travelled through these mountains for centuries.

From the parking lot, it’s about a 700-metre uphill walk on a paved path to the main viewing platform—10-15 minutes for most people, manageable for nearly all fitness levels. The view hits you all at once when you reach the top. For an even higher perspective, continue on the Bow Summit trail for panoramic views of both Peyto and Bow Lakes.

Here’s the timing reality: tour buses start rolling in around 8 AM, and by mid-morning the parking lots can feel more like bus terminals. Arriving before 9 AM or after 6 PM makes a massive difference in your experience. October offers something special—quieter crowds and golden larch trees glowing at higher elevations.

Summer brings that famous turquoise colour, created by glacial rock flour suspended in the water—July and August are the most vibrant. In winter, the lake freezes over and often disappears under snow, trading the turquoise for a more muted but equally striking scene. The parking lot stays accessible year-round, but bring traction devices because the path can get icy.

Mistaya Canyon

Most people skip Mistaya Canyon, which is exactly why you shouldn’t. It doesn’t have the fame of Peyto or the crowds of Johnston, but it’s one of the most visually dramatic spots along the entire Parkway—a narrow slot canyon where the Mistaya River has carved sculptural formations into the limestone over thousands of years.

The trail is short but steep: about 500 metres from the parking lot, downhill on the way in and uphill on the return. At the bottom, a footbridge spans the canyon, and you’ll find yourself looking straight down into churning turquoise water as it swirls through potholes and channels carved by centuries of flow. The shapes in the rock are almost architectural—curves and swoops that look designed rather than natural.

Most people need about 30-45 minutes here, and honestly, you’ll spend a good chunk of that time photographing the formations from different angles. It’s also a perfect midday stop when the sun is too harsh for good lake photography—the canyon stays shaded and interesting regardless of lighting conditions. After 7 PM in summer, you’ll often have the place entirely to yourself.

Winter transforms Mistaya into something otherworldly: frozen formations, ice-coated rocks, and that particular silence that comes with snow. Bring microspikes because the trail gets genuinely slippery, and stay on the marked path—the rocks above the canyon can be dangerous with ice.

Columbia Icefield and Athabasca Glacier

This is the stop that defines the Icefields Parkway—the reason many people make this drive in the first place. The Columbia Icefield is one of the largest accumulations of ice south of the Arctic Circle, a massive frozen plateau that feeds eight major glaciers. And one of those glaciers, the Athabasca, flows right down to the highway where you can actually walk on it.

You’ll see the glacier before you reach it. As you drive north, it appears on your left—a river of ancient ice spilling down from the icefield above, its blue-white surface cracked with crevasses. There’s something almost disorienting about seeing ice on that scale, flowing down a mountain in slow motion. Markers along the road show where the glacier reached in previous decades, each one further down the valley than the last. The retreat is visible and sobering—a reminder that what you’re seeing won’t look the same in another generation.

You can view the glacier from the highway or from the Icefield Centre across the road, but to really experience it, you’ll want to book an Athabasca Glacier tour. The classic option is the Columbia Icefield Adventure: you board a massive Ice Explorer vehicle that drives directly onto the Athabasca Glacier, where you get about 20 minutes to walk on ice that’s around 300 years old. The tour also includes the Glacier Skywalk, a glass-floored platform extending over the Sunwapta Valley that’s either thrilling or terrifying depending on how you feel about heights. The whole experience takes about 2.5-3 hours, and booking ahead is essential in summer.

For a more intimate experience, the Ice Odyssey uses smaller all-terrain vehicles and goes deeper into the glacier’s history and science. And if you want the full immersion, IceWalks runs interpretive tours that take you across the entire tongue of the glacier, including Indigenous storytelling about the cultural significance of ice in these mountains. Those are full-day commitments, but unforgettable.

One thing to be clear about: you cannot walk on the glacier independently, and attempting to do so is genuinely dangerous. The surface is riddled with hidden crevasses and unstable ice, and people have died trying to explore on their own. Only access the glacier through official tours—they know where it’s safe to walk.

If you’re planning to do multiple attractions in the Rockies, the Pursuit Pass can save you 25-40% by bundling the Columbia Icefield Adventure with the Banff Gondola, a lake cruise, Golden Skybridge, and more. It’s valid for the entire season, so you don’t have to do everything in one day. The Value pass starts at CA$271 (with some time restrictions), while the standard Rockies pass at CA$312 offers full flexibility.

Tours run from early May to mid-October, typically 10 AM to 6 PM. Dress warmly—even in summer, you’re standing on ice and the wind can cut through. Sturdy shoes with good grip are essential (not sandals), and bring sunglasses because the glare off the ice is intense. Here’s a money-saving tip: afternoon tours after 3:30 PM are discounted by 20%, and Alberta residents get an additional 20% off.

Even without a tour, the viewpoints and short walks around the Icefield Centre area take about 30-45 minutes and give you a real sense of the glacier’s scale. In winter, the highway stays open but the Icefield Centre and all tours close down. You can still stop and view the glacier from the road, but access is limited and conditions can be extreme.

Note: Due to wildfire damage in 2024, some sections of the Icefields Parkway north of the Columbia Icefield may have restricted stopping. Check 511 Alberta for current conditions before your trip.

Sunwapta Falls

About 55 km north of the Columbia Icefield, you’ll hear Sunwapta Falls before you see it. The Sunwapta River gathers force and plunges into a narrow limestone canyon, the sound building as you walk the short path from the parking lot. It’s an easy stop—the Upper Falls are just a couple minutes from your car—which makes it perfect if you’re running low on time but want one more waterfall fix.

The Upper Falls are the main attraction, a powerful cascade that’s especially impressive from late May through mid-July when snowmelt has the river running at peak volume. But if you’ve got 45 minutes to spare, a 1.3 km trail winds through lodgepole pine forest to the Lower Falls, which are equally dramatic and usually far less crowded. June is typically the sweet spot—maximum water, still relatively early in tourist season.

Like most stops along the Parkway, timing matters. Tour buses make regular stops here, so early morning or after 5 PM gives you breathing room. Afternoon light is best for photography, catching the mist in golden hour.

In winter, the falls don’t stop entirely—water continues flowing beneath layers of ice that build up around the edges, creating sculptural formations that are beautiful in a completely different way. The site is accessible year-round, but the trails get icy, so watch your footing.

Athabasca Falls

The final major stop before Jasper, and it’s a showstopper. Athabasca Falls isn’t particularly tall—about 23 metres—but the sheer volume of water crashing through the narrow canyon is staggering. The Athabasca River is one of the largest in the Rockies, and watching all that water force itself through such a tight gap gives you a visceral sense of nature’s power.

Over thousands of years, that power has carved potholes and channels into the hard quartzite rock, creating formations you can walk around and peer into via a network of short, paved trails. A footbridge spans directly over the gorge, and on sunny afternoons, the spray creates rainbows that hover in the mist. It’s one of those places where you’ll take way more photos than you planned to.

Most people spend 20-45 minutes exploring all the viewpoints. Like everywhere along the Parkway, tour buses make regular stops, so before 8 AM or after 5 PM is your best bet for a quieter experience. Late May through July offers the highest water flow, when the falls are at their most thunderous.

In winter, portions of the falls freeze into dramatic ice formations while water continues to flow beneath and through them—it’s a completely different scene, stark and beautiful. The trails can get icy, so bring traction, but the parking lot stays accessible year-round.

And then, just 30 km up the road, Jasper awaits.

Arriving in Jasper

From Athabasca Falls, it’s about 20 minutes to the town of Jasper. If you started early in Banff, you’ll likely roll in during late afternoon—perfect timing for wandering the main street, grabbing dinner, and letting the day’s images settle in your mind. The mountains glow golden at sunset here, and after a full day of driving and stopping and photographing, there’s something deeply satisfying about just sitting somewhere with a drink and watching the light change.

Driving back to Banff the same day is technically possible, but it’s long—about four hours without stops, and you’ll be tempted to stop. Many people prefer to spend a night in Jasper and make the return drive the next day. You’ll catch things you missed, see familiar viewpoints in completely different light, and arrive back in Banff actually rested. The Parkway is beautiful in both directions.

One last practical note: fill up in Jasper before heading back. The next gas after Jasper is at Saskatchewan River Crossing, about 150 km south, and if that’s closed for the season, you’ll be pushing it to make Lake Louise.

Bonus: Viewpoints, Detours, and Hidden Stops

Beyond the major stops, the Icefields Parkway is lined with pullouts and viewpoints that don’t always make the highlight reels but are absolutely worth your time. Part of the magic of this drive is the unplanned stops—the places you pull over simply because something catches your eye.

Glacier Viewpoints Along the Way

You don’t have to set foot on a glacier to appreciate them. The Parkway offers dozens of viewpoints where you can see glaciers clinging to mountain peaks, and most are just a short walk from roadside pullouts. Crowfoot Glacier, visible from a viewpoint just north of Bow Lake, got its name because it once resembled a crow’s three-toed foot—though climate change has melted away one of those “toes” in recent decades. The Weeping Wall, a cliff face that streams with waterfalls in summer (and becomes an ice climbing destination in winter), appears on your left as you drive north. And throughout the drive, you’ll catch glimpses of the Wapta Icefield, the Waputik Icefield, and countless unnamed glaciers tucked into high valleys. Keep an eye on the peaks—there’s almost always ice up there somewhere.

Several interpretive pullouts have signs explaining what you’re looking at and the geology behind it. These are great spots to stretch your legs without committing to a full hike. The Parkway was designed with these viewpoints in mind, and the road engineers knew exactly what they were doing when they carved out those parking areas at the best angles.

One tip: the light changes everything. A glacier that looks flat and grey at midday can glow blue and white in the golden hour. If you’re driving back to Banff and have time, consider stopping at viewpoints you passed earlier in the day—the afternoon light often reveals details you missed in the morning.

Saskatchewan River Crossing

About 85 km north of Lake Louise, Saskatchewan River Crossing sits at the junction of the Icefields Parkway and the David Thompson Highway (Highway 11). It’s the only facility between Lake Louise and the Columbia Icefield, which makes it a natural rest stop—and frankly, a bit of a relief after an hour and a half without services.

The Crossing Resort has fuel (expect to pay a premium for the convenience), a restaurant, gift shop, and basic supplies. There’s also limited EV charging at the gas station. It’s a good place to stretch your legs, use proper restrooms, and grab a coffee before tackling the next stretch of highway.

One important caveat: the resort closes for winter, typically November through April. If you’re driving the Parkway in the off-season, fuel up in Lake Louise or Jasper—there’s nothing in between.

Abraham Lake

If you turn east onto Highway 11 at Saskatchewan River Crossing, you’ll reach Abraham Lake in about 32 km. In summer, it’s a beautiful turquoise lake with dramatic mountain backdrops—less famous than the lakes in Banff, and far less crowded. But winter is when Abraham Lake becomes something truly special.

The lake is famous for its frozen methane bubbles, one of the most unique natural phenomena in the Rockies. As vegetation on the lakebed decays, it releases methane gas that rises toward the surface. When the lake freezes, those bubbles get trapped in layers, creating stacked columns of white orbs suspended in crystal-clear ice. It looks like something from another planet, and photographers travel from around the world to capture it.

The best time to see the bubbles is late December through February, when the lake is frozen solid but not yet buried under snow. You need clear ice, which means timing and weather conditions matter. The main viewing spot is Preacher’s Point, about 32 km east of Saskatchewan River Crossing, with several other pullouts offering lake access along the next 20 km of highway.

A few things to know: ice cleats are essential because the frozen lake is brutally slippery. Dress for serious winter conditions—wind protection, extra socks, hand warmers. There’s no cell service out here, and in winter, the gas station at Saskatchewan River Crossing is closed, so fuel up in Lake Louise or Jasper before heading out. But if you’re in the Rockies during winter and have a free day, Abraham Lake is absolutely worth the detour.

Last updated: January 2026. Check the Parks Canada website and 511 Alberta for current road conditions and seasonal closures before your trip.